Lasers

I like laser pointers quite a lot. It is empowering to merely press a button and see the result instantaneously appear on a physical surface a great distance away. It helps in this regard that since pointing at a screen significantly reduces laser intensity, many commercial laser pointers are very bright, and often close to the federal intensity limit of 5 milliwatts (which, funnily enough, is regulated by the FDA, even though the main safety issue is lasers pointed at airplanes, which is reported to the FAA. Such is the nature of bureaucracy.)

In fact, the best (and one of the hardest) escape room puzzles I've seen was to reflect a laser beam, using two small hand mirrors, to hit a target in another room.

Given how fun that task was, I wanted to see how far it could be extended, so I recruited a couple friends one night to try to reflect a beam across campus using mirrors. Brown's campus is organized around a roughly plus sign-shaped series of open green areas, so I'd thought we could get the beam from one end to the other with just two or three mirrors. Any more than that, and the human error in each reflection makes the beam wildly unstable. Handling the wobbling from just the two mirrors we had immediate access to was very difficult, and buildings in the way and elevation change make the difficulty of crossing large distances even greater.

Eventually, we had to settle on aiming from the front of the engineering building, across Brook Street, the Sciences Quad, Thayer Street, and Simmons Quad to hit the statue of Mark Antony in the face (which is still no small distance; see Figure 1). It was past midnight, so not too many cars were passing, but we still had to pause occasionally for passers-by or the Brown University Shuttle (BUS) doing its rounds.

Fig 1. The beam's path, from right to left, in Google Maps

The next problem with this plan is that, as tightly concentrated into one point as a laser beam is, it still spreads out over time. After crossing two streets like we did, the beam was a couple feet wide, and each wobble of a millimeter of my hand by the engineering building would send the beam careening by yards over by the statue. Fortunately for us, one of the table mirrors we were using had a concave side that we could use to focus the beam a little, and then use the other flat mirror to aim at Antony.

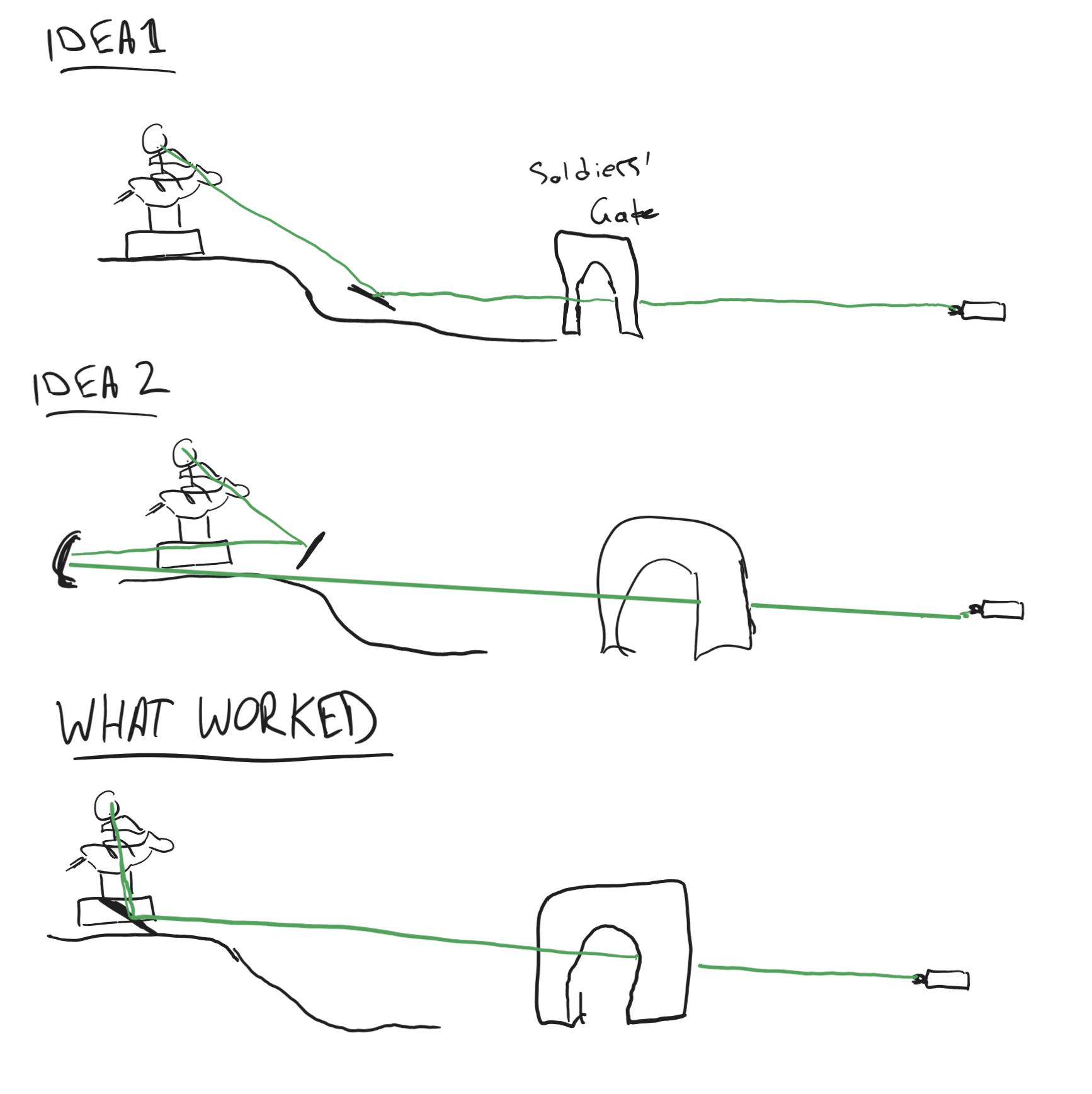

By far the main issue, however, was what angles to use to reflect the beam. Since the beam passed under an arch on its way from the engineering buildling to Simmons Quad, and the statue is on a slight hill, it's impossible to just hit Antony's face directly - the top of the arch is blocking it. If you try to angle the beam up from the bottom of the hill, at a very small angle of incidence (that is, redirect the beam only very slightly), the wobbling is too much to be accurate.

Our next idea was to shine the beam past the statue, reflect it back and narrow it with the concave mirror, and then reflect it forward again to hit the statue. The nearly 180° reflections give you much greater control, and this came close to working. But the concave mirror only narrows the beam up to a short distance away, beyond which it spreads out again. And in the end, it turned out that having two mirrors introduced too much wobbling over too great a distance to be viable.

After about an hour of fiddling, with one person standing directly under the statue and angling the beam straight up to the statue using a flat mirror, we finally managed to hit Mark Antony in the face pretty consistently, and get a picture (Figure 3). It was a satisfying result, but I don't think I'll be going into optics anytime soon.

Fig 2. Beam angling strategies

Fig 3. The laser beam on Mark Antony's face, finally